Mitigation Status and Context:

Greenhouse gas emissions are the result of combustion of imported fossil fuels in the energy sector for:

- Electricity generation;

- Sea transport;

- Land transport;

- Kerosene for lighting on outer islands; and

- LPG and kerosene for cooking.

The vision for the Kiribati National Energy Policy (KNEP) is “available, accessible, reliable, affordable, clean and sustainable energy options for the enhancement of economic growth and improvement of livelihoods in Kiribati.” Reducing fossil fuel imports is the major goal, with the uptake of renewable energy along with further energy efficiency improvements on both the demand and supply sides, expected to replace more than one-third of fossil fuels for electricity and transport by 2025.

Reflecting the ambition of the Majuro Declaration2, Kiribati has identified targets focused on reductions in fossil fuel use by 2025 through increases in renewable energy and energy efficiency (RE and EE) in the following sectors and geographical areas:

- South Tarawa by 45% (23% RE and 22% EE);

- Kiritimati Island by 60% (40% RE and 20% EE);

- rural public infrastructure, including Southern Kiribati Hospital and Ice plants by 60% (40% RE and 20% EE); and

- rural public and private institutions such as boarding schools, Island Council, private amenities and households by 100%(100% RE).

Actions

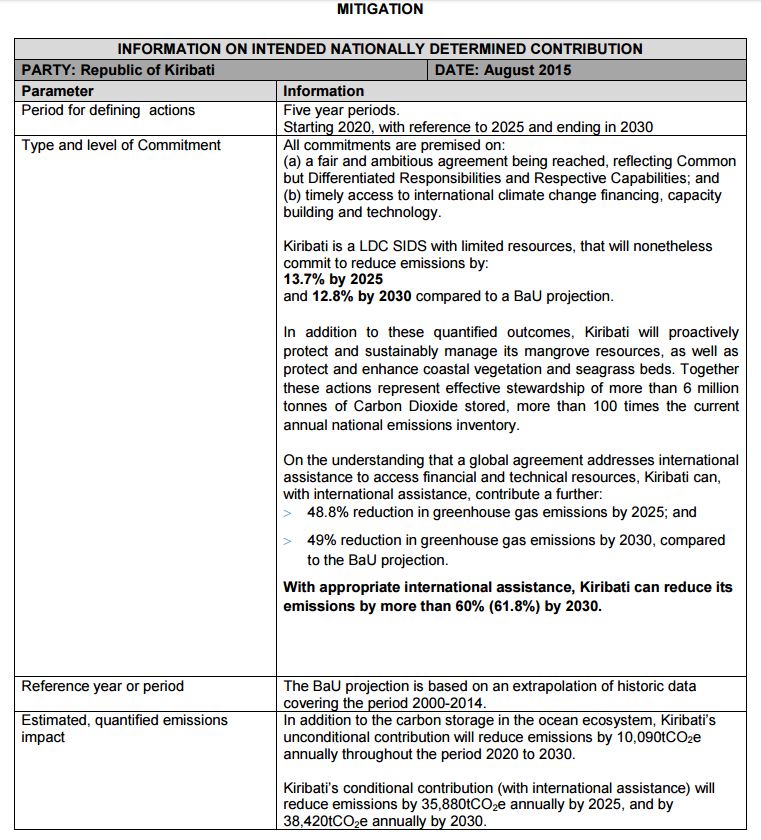

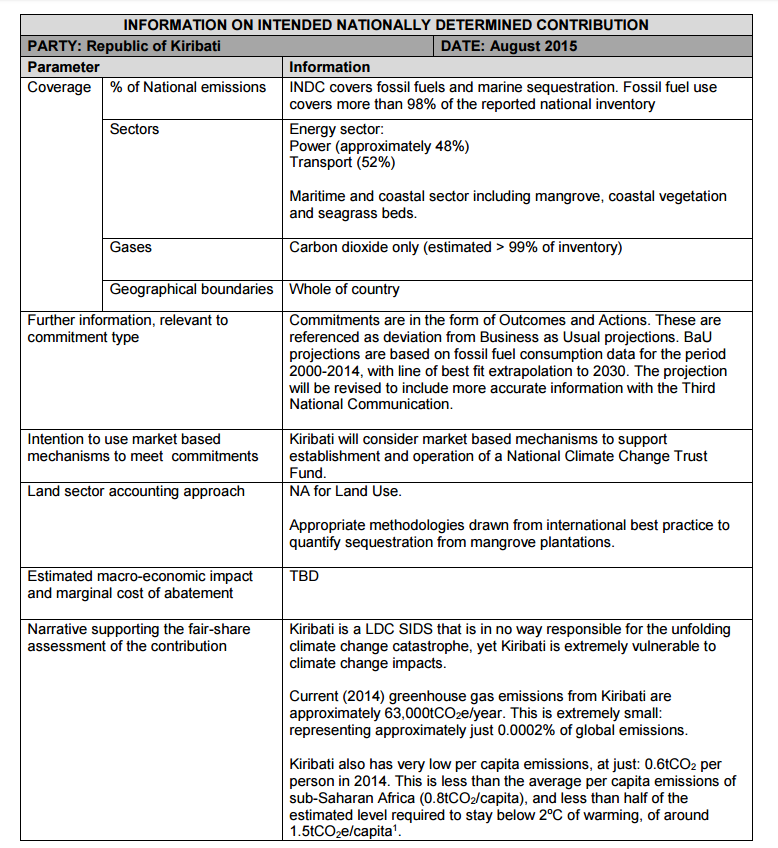

In preparing its INDC, Kiribati considered mitigation actions that were currently planned and funded (as the Kiribati Contribution), and those that have been identified as technically viable with current technology suitable to the Kiribati context (as the Contribution conditional on adequate and timely international assistance), summarised in the Table below.

2 ‘Majuro Declaration for Climate Leadership’ 2013. Pacific Islands Forum Leaders’ Meeting, Majuro, Republic of Marshall Islands.

To be realised, the conditional mitigation Actions require a timely combination of capacity building, technology transfer, and financial support, primarily in the form of grants. Additional mitigation actions may be identified in the future.

Below is a brief summary of the activities proposed for off-grid electricity production, with estimates of financial resources required (in AUD):

- Activity 1 – Solar PV mini grid system for Southern Kiribati Hospital (2.4 million) - design, procure and install off-grid PV systems for the Southern main hospital (265kWp) to a level to support the fully equipped needs to operate the hospital. (not yet fully funded)

- Activity 2 – Outer Island Clinic solar system rehabilitation ($230,000.00) - design, procure, and install 58 systems in total on 20 outer Islands to provide power for lighting and for HF communication radio. (not yet fully funded)

- Activity 3 – Mereang Taabwai Secondary Schools solar PV mini-grid ($500,000.00) - design, procure and install off-grid PV systems (20 kWp) for the school to a level to

support a fully equipped computer lab, dormitory lighting, refrigerator/freezers, office equipment and audio-visual equipment. (funded/under implementation)

- Activity 4 –Junior Secondary School (JSS)system.($285,000.00) - design, procure and install off-grid PV systems for lighting and Charging Laptop computers of 2 classrooms and staff room in all JSS in the Outer Islands (410 Wp each). (not yet fully funded)

- Activity 5 –Solar Home System for Households.(1.5million) - procure and install 3900 solar home system to cover up all remaining households in the Outer Islands. The system will provide basic lighting, phone and radio charging which will improve social- economic condition in the Outer Islands. (funded/under implementation)

- Activity 6 – Outer Island Council solar PV mini grid system ($710,000.00) - design, procure and install off-grid PV systems (5 kWp each) for island council administrative centres in the Gilbert and Line Groups. (not yet fully funded)

- Activity 7 – Outer Island Fish Centres ($610,000.00) - design, procure and install off-grid PV systems for the Fish Centres (3.75kWp each) in all the Islands to a level to support a fully equipped centres lighting, refrigeration and other equipment. (not yet fully funded)

- Activity 8 – Desalination Plant for vulnerable rural community. ($115,000.00) – 19 systems for 12 community systems for solar water desalination plant will be procured and installed on 9 selected Islands. This activity will improve quality of life in households by providing portable water supply to the most vulnerable Islands in Kiribati. (not yet fully funded)

- Activity 9 – Outer Island Police Station solar system rehabilitation ($60,000.00) - 23 solar systems (120 Wp each) will be procured and installed in all of the outer Islands for communication, lighting, etc at the Police stations and an additional 8 Police posts. (not yet fully funded)

- Activity 10 – Solar PV system for non-government vocational institutions: CCL Manoku and Alfred Sadd Institution ($500,000.00) - design, procure and install off-grid PV systems (10 kWp) for each community institution to support the institution daily activities. (funded/under implementation)

ADAPTATION

Kiribati has been working actively on climate change adaptation for 20 years, and with the development of pioneering tools and methodologies that are regarded as best practices regionally and internationally, has made and continues to make a considerable contribution to the global and regional adaptation planning and management process and pool of knowledge on building climate resilience. This contribution is made in the face of severe constraints and challenges confronted by Kiribati as a small island developing States (SIDS) and Least Developed Country (LDC). For Kiribati, where climate change threatens the very existence of the nation and population, adaptation is not an option – but rather a matter of survival.

Current climate, projected climate change and related assumptions

Kiribati has a hot, humid, tropical climate with an average air temperature of 28.3°C and average rainfall of about 2100 mm per year in Tarawa (1980–1999). Its climate is closely related to the temperature of the oceans surrounding the small islands and atolls. Across Kiribati the average temperature is relatively constant year round. From season to season the temperature changes by no more than about 1°C. Kiribati has two seasons – te Au Maiaki, the dry season and te Au Meang, the wet season. The periods of the seasons vary from location to location and are strongly influenced by the seasonal movement of the South Pacific Convergence Zone (SPCZ) and the Inter-tropical Convergence Zone (ITCZ).

The six-month dry season (te Au Maiaki) for Tarawa starts in June, with the lowest mean rainfall in October. The wet season (te Au Meang) starts in November and lasts until April; the highest rainfall occurs from January to March, peaking with a mean of 268 mm in January. The highest rainfall usually occurs when the ITCZ is furthest south and closest to Tarawa; there are also high rainfalls, though to a lesser extent, when the SPCZ is strongest. The average sea-surface temperature of oceans around Kiribati is 29.2°C (1980–1999). As Kiritimati is 2000 km to the east from Tarawa, its wet season starts at a different time, from January to June, with the wettest months being March and April. Rainfall in the northeast of Kiribati is only affected by the ITCZ.

Across Kiribati there is a change in mean monthly rainfall towards the end of the year. There is however, a large variation in mean annual rainfall across Kiribati. A notable zone of lower rainfall, less than 1500 mm per year exists near the equator and extends eastwards from 170°E. On average, Tarawa at 1.1416ºN receives just under 2100 mm, while the island of Butaritari at 3.1678ºN only 350 km to the north, receives around 3000 mm. The climate of Kiribati, especially rainfall, is highly variable from year to year. Tarawa, for example, receives more than 4000 mm of rainfall in the wettest years, but only 150 mm in the driest. This huge range is similar in Kiritimati and has enormous impacts on water availability and quality, crop production, food security and health. The main reason for this variability is the El Niño–Southern Oscillation (ENSO). Many Kiribati islands lie within the equatorial waters that warm significantly during an El Niño event and cool during a La Niña event. As a result rainfall is much higher than normal during an El Niño and much lower during a La Niña. Maximum air temperatures tend to be higher than normal during El Niño years, driven by the warmer oceans surrounding the islands, while in the dry season minimum air temperatures in El Niño years are below normal. At Kiritimati, El Niño events also bring wetter conditions in both seasons and La Niña events bring drought. El Niño is generally associated with above-normal rainfall and strong westerly winds, while La Niña is associated with below-normal rainfall and the risk of drought.

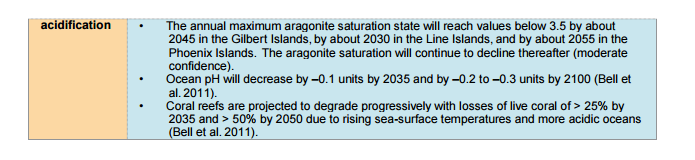

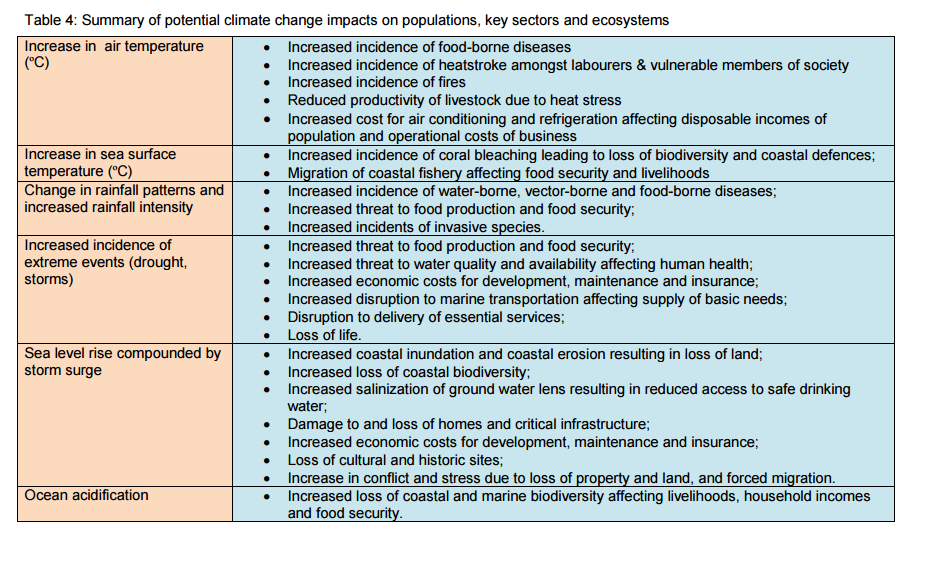

The climate of Kiribati is changing and will continue to change in the future as a result of global climate change. Table 2 summarises the trends already observed in variables such as temperature, rainfall, sea level, extreme events and ocean acidification in Kiribati.

With many islands situated at 2 meters or less above sea level, Kiribati has already witnessed first hand the impacts of global climate change. According to the Pacific Regional Environment Programme (SPREP), two small uninhabited Kiribati islets, Tebua Tarawa and Abanuea, disappeared underwater in 1999. The United Nations Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change predicts that sea levels will continue to rise due to climate change, and it is thus likely that within a century the nation's arable land will become subject to increased soil salination and will be largely submerged, while other islands and atolls will share a similar fate to Tebuatarawa and Abanuea and disappear altogether.

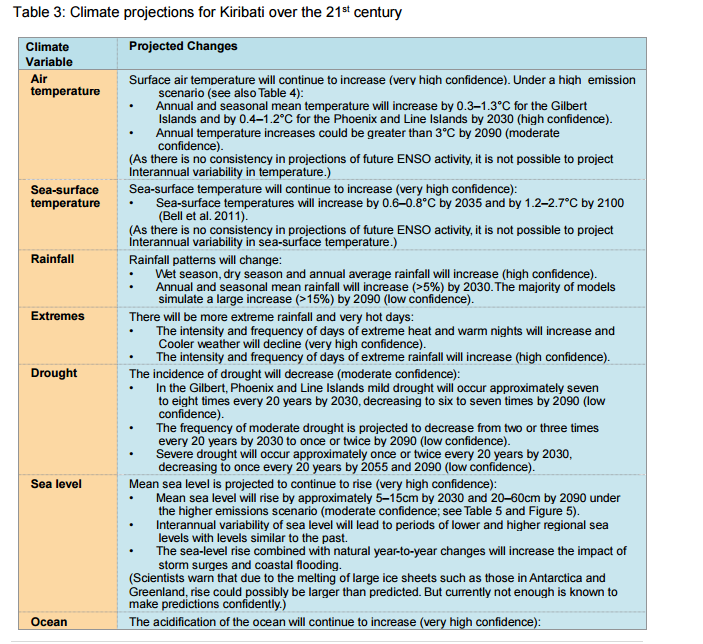

Table 3 provides climate change projections for Kiribati are based on up to 18 global climate models for up to three emission scenarios – low, medium and high – and three 20-year periods

– centred on 2030, 2055 and 2090, relative to 1990. There is no single projected climate future for Kiribati, but rather a range of possible futures. Projections represent an average change over either the whole of Kiribati or over smaller but still broad geographic regions such as the Line Group. However, projections are not for specific locations such as towns. The projections listed in Table 3 are presented along with confidence levels based on expert judgement by scientists who conducted the analysis. The levels range from very high, high and moderate to low confidence.

Past La Niña events have shown that the impacts of droughts can be very severe in Kiribati. For example, in 1971, 1985, 1998 and 1999, annual rainfall was less than 750 mm. The recent drought from April 2007 to early 2009 severely affected the southern Kiribati islands and Banaba. During this period, copra production significantly declined, depressing the outer island economies which rely on copra as a main income source. The groundwater also turned brackish and the leaves of most plants turned yellow. During the 1970–1971 drought, a complete loss of coconut palms was reported at Kenna village on Abemama in central Kiribati.

The country is located in relatively calm latitudes but its low atolls (in many places no more than 2m above mean sea level and only a few hundred meters wide) are subject to long-term sea level rise and, more immediately, are exposed to continuing coastal erosion and inundation during spring tides, storm surges and strong winds. The islands are subject to periodic storm surges with a return period of 14 years. By 2050, 18-80% of the land in Buariki, North Tarawa, and up to 50% of the land in Bikenibeu, South Tarawa could become inundated. As a result of ENSO events, Tarawa already experiences significant natural fluctuations in sea level of about

1.5 metres. These fluctuations will affect the inundation potential of the atoll, particularly when combined with storm surges and the projected increase in sea level. The low-lying places along the atolls have already experienced coastal inundation from unexpected extreme high tides. The extreme high tides, when they coincide with the spring tide, result in a threshold of >2.8 metres, as in 2010 when wave overtopping damaged infrastructure and properties. Because of narrow islands, the entire population and most infrastructure and agricultural production is concentrated along the coast making it directly exposed to these climatic threats. The results of sea level rise and increasing storm surge threaten the very existence and livelihoods of large segments of the population, increase the incidences of water-borne and vector-borne diseases undermining water and food security and the livelihoods and basic needs of the population, while also causing incremental damage to buildings and infrastructure.

Analysis of vulnerable sectors and segments of society

Kiribati is one of the most vulnerable countries in the world to the effects of climate change. The country’s ability to respond to climate risks is hampered by its highly vulnerable socio-economic and geographical situation. Low atolls, isolated location, small land area separated by vast oceans, high population concentration, and the costs of providing basic services make Kiribati, like all Small Island Developing States (SIDS), especially vulnerable to external shocks including the adverse impacts of climate change. Sea-level rise and exacerbated natural disasters such as drought and weather fluctuations pose significant and direct additional threats to sectors and resources central to human and national development and the provision of basic human needs.

The following factors are contributing to the nation’s vulnerability to climate change and disaster risks, which apply across the various sectors:

- A high population and growth rate on South Tarawa in the Gilbert Group (50,182 inhabitants with a population density of 3,184 persons per square kilometer) as well as on Kiritimati in the Line Islands Group (5,586 inhabitants), which is due to: a high proportion of children and youth, high levels of fertility, low rates of contraceptive use, and disparities between the different islands of Kiribati (resulting in internal migration, displacement, and urbanisation), all effecting the resilience of the population and natural ecosystems;

- In fast-growing urban areas, especially South Tarawa with a growth rate of 4.4% and to a certain extent also North Tarawa and Kiritimati, the population pressure and lifestyle changes have strained the already limited freshwater resources - in many areas, the freshwater consumption rates are already exceeding the estimated sustainable yield of groundwater sources (such as in the Bonriki and Buota Water Reserves on South Tarawa);

- The increase in non-biodegradable waste usage in urban areas, as well as poor waste and sanitation management, result in limited access to unpolluted land and sea, degradation of land and ocean based ecosystems, and numerous isolated occurrences of diarrhoeal and vector borne diseases, all affecting the resilience of the population and natural ecosystems;

- Traditional food systems are declining in favour of imported food, and the number of people who preserve and apply traditional knowledge is decreasing, affecting food security;

- In rural outer islands, the people have limited access to employment opportunities, effective transport, communication, and community services such as education and health - these factors, combined with a high dependency on subsistence agriculture and coastal fisheries, make rural communities more vulnerable;

- Government revenue is declining and highly dependent on fisheries revenue (40– 50%) with limited capacity to maximise the benefits of these resources;

- Many laws do not take into account sustainable management concerns, climate change predictions and disaster risks;

- Safety and emergency response capacities of Kiribati are limited;

- The low-lying atoll islands are already experiencing severe coastal erosion and inundation due to natural and human causes, leading to a loss of land, public and private buildings, and infrastructure.

In the long-term, the most serious concern is that sea-level rise will threaten the very existence of Kiribati as a nation. But in the short to medium term, a number of other projected impacts are of immediate concern. Of particular note is the concern as to whether the water supply and food production systems can continue to meet the basic needs of the rapidly increasing population of Kiribati.

The effects of climate change are felt first and most acutely by vulnerable and marginalised populations, including women, children, youth, people with disabilities, minorities, the elderly and the urban poor. Violence against women and children is a widespread issue within Kiribati society, which can be exacerbated in times of disasters when normal social protection may be missing. In addition, the population is facing stress due to the uncertainty over their livelihood, culture and homeland. Climate variability, climate change and disaster risks, in combination with the factors that make Kiribati particularly vulnerable to them, are affecting the environment and all socio-economic sectors, including agriculture, education, fisheries, freshwater, health, infrastructure, trade and commerce.

National Adaptation Efforts including International and Regional Support for Adaptation

The Kiribati government first became aware of climate change and sea level rise in the early 1990’s, and requested scientific advice on whether there was any real cause for concern about sea level rise. The earliest studies could not provide information in that regard, but they were useful in making the Kiribati government more aware and knowledgeable about its geophysical environment and ecosystems, and sea level changes over the geological time span.

Subsequently but still during the early 1990s, more detailed studies were undertaken. A study area on a small island in Tarawa suggested certain areas to be liable to flooding from storm surges. This has been vindicated during storm surges in the 2000s. A study of Kiritimati island, which is the largest atoll in Kiribati and indeed in the world, indicated that the land had been rising. These studies, however, did not provide or take into account any sea level rise scenarios.

The US Country Study Programme, starting in 1995, was the first climate change project, and focussed on developing a country profile for Kiribati. Subsequently, the Kiribati Initial National Communication submitted to the UNFCCC in 2000 was one of the outputs of the Pacific Islands Climate Change Assistance Programme3 to which Kiribati participated. Since the completion of the Initial National Communication, several studies and assessments have been undertaken by various international institutions on various vulnerable sectors relevant to climate change in Kiribati. These studies are important undertakings to highlight key vulnerabilities in Kiribati which require adaptive actions.

After PICCAP, funding for various enabling activities to be undertaken by LDCs was established in a decision of the UNFCCC, including the development of National Adaptation Plans of Action. Kiribati participated in the development of the NAPA and working with UNDP completed its NAPA document and submitted it to the UNFCCC in 2007. Concurrently with the preparation of the NAPA, Kiribati welcomed a World Bank initiative to start the Kiribati Adaptation Project (KAP) with co-finance from Government of Japan. The initial phase of KAP under the World Bank focussed on the preparation of Adaptation Project Implementation Plan for the second phase, and studies that were considered necessary to guide and inform a mulit-year program on adaptation.

The second phase of KAP, that is KAP II, was completed in 2011 with many technical assessments produced on the coastal vulnerability relative to sea level scenarios, droughts information, water planning, design of coastal protection leading to the construction of some coastal protection structures, rainwater harvesting and construction of a community infiltration gallery in North Tarawa, and other improvement works on South Tarawa water supply.

The Kiribati Adaptation Program-Phase III (KAP III) builds on KAP II best practices in designing and implementing adaptation measures in water and civil works. The Project is being implementing physical investments and capacity building; emphasize community consultation/participation; and leverage other donor activities in pursuing climate resilient investments. It is expected that the project will move quickly to the implementation of investments on the basis of the extensive technical and analytical work already carried out during the preparation and implementation phase of KAP II. KAP III activities represent both climate change adaptation and natural hazard disaster reduction measures. In particular,

3 The PICCAP was executed through the South Pacific Regional Environment Programme (SPREP) with funding provided by the Global Environment Facility (GEF).

expansion of the ground water reserves is crucial to managing severe droughts which impose severe public health risks on Tarawa and require national emergency response. The proposed shoreline protection investments mitigate the effects of erosion of assets in the coastal zone,

e.g. roads, and retain the width of water reserves to sustain freshwater lenses. KAP III main activities include: (i) improvements to water resource use and management with primary sub components of groundwater abstraction system; water reticulation including leakage detection; up-gradation of water supply at Tungaru Hospital; community awareness about water conservation; feasibility of developing treated water resources in South Tarawa; water legislations, etc. (ii) enhancement in costal resilience with primary emphasis on continuation of shoreline protection works in South Tarawa; and advisory support and asset management of coastal infrastructure; (iii) institutional strengthening; and (iv) project management.

Funds for these adaptation projects have been from a variety of bilateral and multi-lateral grants. The principal delivery mechanism for climate change adaptation programs in Kiribati has been through intermediary organisations such as the World Bank, UNDP, UNEP, various bilateral organisations, and regional agencies such as SPC and SPREP. Currently, Kiribati is working with the World Bank, UNDP and SPREP to prepare adaptation projects for funding under the Green Climate Funds and the Global Environment Facility (GEF).

Adaptation Policy and Programs - Nationally determined adaptation needs, options, adaptive capacity enhancement

A whole-of-nation approach is being pursued by government to address the impacts of climate change and sea level rise and related environmental issues in Kiribati. Climate change and disaster risks are being addressed in policies and strategies relating to population, water and sanitation, health and environment. Similarly disaster risk management is progressively being incorporated into policies and strategies relating to fisheries, agriculture, labour, youth and education. The new Kiribati Integrated Environment Policy encourages all government programs to collect, manage and use environmental data to safeguard the environment and strengthen resilience to climate change and disasters.

The KiribatiDevelopmentPlan(KDP) 2012–2015 is the overarching national development plan detailing national priorities. The KDP is linked to the Millennium Development Goals, the Pacific Plan and the Mauritius Strategy for Small Island Developing States (BPoA+10). The KDP has six broad key policy areas (KPAs). Climate change is incorporated into KPA 4 on environment, providing the link to the KJIP. The key objective of KPA 4 is to facilitate sustainable development by mitigating the effects of climate change through approaches that protect biodiversity and support the reduction of environmental degradation by the year 2015.

The National Adaptation Program of Action (NAPA) (2007) sets out a 3 year plan for urgent and immediate actions in the Republic of Kiribati to begin work in adapting to climate change. The goal of the NAPA was to contribute to and periodically complement a long term framework of adaptation through identifying immediate and urgent adaptation needs that are consistent with national development strategies and climate change adaptation policies and strategies. The objective is to communicate in a simplified way the identified immediate and urgent adaptation needs of Kiribati, which is also relevant to the national communication obligation required by the UNFCCC. These adaptation needs are identified through a participatory, consultative and multidisciplinary planning process. The NAPA outlines 9 priority projects valued at US$11.983 million to address short-term (3 years) needs in critical sectors (water, coastal zone

management, agriculture, coastal infrastructure) and to strengthen national adaptive capacity and information systems.

The National Framework for Climate Change and Climate Change Adaptation (April 2013) establishes a framework for an effective national response to address the impacts of climate change that requires that climate change and climate change adaptation assume a prominent role within the national development planning process. This process is comprised of five main parts that include long range policy and strategy statements, namely: Kiribati Development Plan (KDP), annual GoK Budget, multi-year budget framework and Ministry Operational Plans (MOPs) and Public Enterprise Business Plans (PEBPs). This document extends the 2005 Climate Change Adaptation Strategy which was developed as part of the World Bank funded Kiribati Adaptation Project. Under this strategy the following five headings outline Kiribati action to strengthen its capability to meet the challenge of climate change. These are:

- Mitigation - aim to improve energy efficiency and enhance the use of renewable energy both on the main islands and in the outer islands;

- Integration of climate change and climate change adaptation into national planning and institutional capacity – aim to integrate climate change adaptation considerations into Kiribati Development Plan (KDP), annual GoK Budget, multi-year budget framework and Ministry Operational Plans (MOPs) and Public Enterprise Business Plans (PEBPs);

- External financial and technical assistance - have international climate change funds channeled directly into the mainstream activities of line Ministries involved with climate change adaptation as direct budget support as a national priority;

- Population and resettlement – aim to reduce the vulnerability of Kiribati to increasing physical risks caused by climate change by establishing host country agreements to government-sponsored and self-sponsored emigration to resettle I-Kiribati overseas and assist the inevitable migration of the population, due to climate change as and when this eventually arrives;

- Governance and services – aim to improve policy coordination and planning on climate change adaptation, strengthen capacity of government to implement climate change adaptation measures, and build improves technical services capacity to address risks from climate change;

- Survivability and self-reliance – ensure that risks associated with climate change and the intellectual and practical processes for the planning for the consequence of climate change are undertaken at the earliest opportunity.

The KiribatiJointImplementationPlanon Climate Change and Disaster Risk Management (KJIP) (2014) has been developed to reduce the vulnerabilities to the impacts of climate change and disaster risks and to coordinate priorities so that investments will derive maximum value. The KJIP is part of the commitments Kiribati made under the Pacific Islands Framework for Action on Climate Change (PIFACC), the Regional Framework for Action on Disaster Risk Management endorsed by the Pacific Leaders in 2005 and the Pacific Islands Meteorological Strategy (PIMS) approved in 2012. The KJIP is consistent with these three inter-related regional frameworks, specifically in terms of the national priorities for actions. As party to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC), the Government sees the KJIP as its National Action Plan on climate change. Similarly, the KJIP is contributing to the implementation of the Hyogo Framework for Action (2005–2015) under the United Nations International Strategy on Disaster Risk Management (UNISDR) and the Climate Services priorities of the World Meteorological Organisation (WMO). The vision of the 9-year KJIP (2014 – 2023) is:

I-Kiribatiuniqueculture,heritageandidentityareupheldandsafeguardedthrough enhanced resilience and sustainable development.

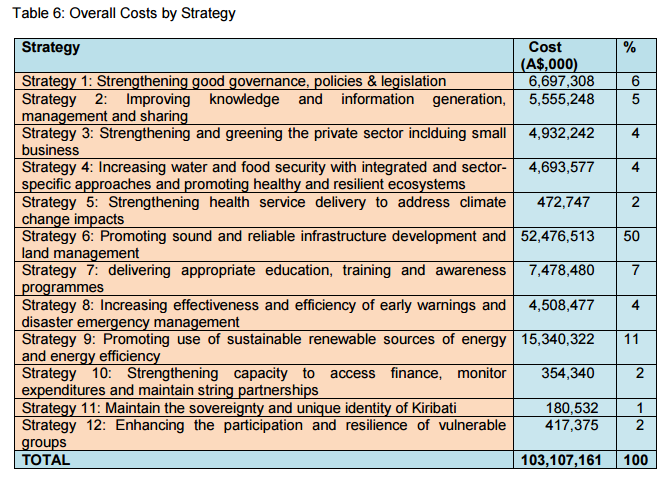

The goal of the KJIP is to increase resilience through sustainable climate change adaptation and disaster risk reduction using a whole of country approach. To reduce vulnerabilities and respond to observed and likely impacts of climate change and disaster risks, the KJIP identifies 12 major strategies, as follows:

- Strengthening good governance, policies, strategies and legislation;

- Improving knowledge and information generation, management and sharing;

- Strengthening and greening the private sector, including small-scale business;

- Increasing water and food security with integrated and sector-specific approaches and promoting healthy and resilient ecosystems;

- Strengthening health-service delivery to address climate change impacts;

- Promoting sound and reliable infrastructure development and land management;

- Delivering appropriate education, training and awareness programmes;

- Increasing effectiveness and efficiency of early warnings and disaster and emergency management;

- Promoting the use of sustainable renewable sources of energy and energy efficiency;

- Strengthening capacity to access finance, monitor expenditures and maintain strong partnerships;

- Maintaining the sovereignty and unique identity of Kiribati;

- Enhancing the participation and resilience of vulnerable groups

Each strategy has one or more key actions, sub-actions, outcomes and performance indicators (outcome- and output-based) to address climate change and disaster risks in response to the identified vulnerabilities and impacts. Detailed strategic plan with key actions, sub-actions, results and performance indicators, lead and support agencies and partners associated with each strategy, are provided as an Annex to the KJIP. All strategies and actions in the KJIP are inclusive of vulnerable groups, considering gender, youth and children, the elderly and people with disabilities.

Adaptation Capacity, Including Engagement of Private Sector and Civil Society in Adaptation and Climate Resilience Building

The implementation of priority adaptation measures face serious institutional challenges such as a high staff turnover rates in senior executive positions, limited sector specific training, and a lack of clarity on internal roles and responsibilities. Furthermore, there are constraints on adaptation knowledge sharing, coordination and collaboration among ministries as well as with nongovernmental organisations (NGOs), the private sector, faith-based organisations and development partners.

There continues to exist knowledge, skill level and capacity gaps with regards to climate change adaptation and disaster risks throughout Kiribati society, particularly in the outer islands and among marginalised populations. A key challenge is to translate the climate science and predicted impacts into messages that the I-Kiribati population can relate to. In some instances there are cultural and religious barriers to awareness and action, such as cultural practices of guarding traditional knowledge and religious beliefs. There is very limited capacity at the community level to undertake local level vulnerability mapping, adaptation planning and the implementation of priority adaptation interventions.

In 2007, Kiribati participated in a GEF-funded National Capacity Self Assessment (NCSA) to evaluate capacities for the implementation of the Rio Conventions, including the UNFCCC. A report on the thematic area of climate change was produced. The Report documents that the first climate change project undertaken by Kiribati government that focussed on capacity building was the US funded Climate Change In Country Studies. Key outputs of the project included:

- Institutional strengthening for climate change planning within the Environment and Conservation Division;

- The setting up of a Climate Change Study Team;

- Capacity building in understanding important resources such as the fresh ground water lens;

- Analysis of local climate data for comparison with global situation as given in IPCC Assessment Reports; and

- Incentives for officials to make efforts to understand certain IPCC Technical Reports.

Members of the Climate Change Study Team included representatives of key sectors such as meteorological services, water, land management, mineral resources, fisheries, public health, agriculture, energy, economic planning, and education. The private sector was represented by the USP Kiribati Centre. It was chaired by the most senior official of the Environment and Conservation Division, with a project coordinator being a member.

Capacity building continued under the Pacific Islands Climate Change Assistance Programme (PICCAP). Under this programme, the Climate Change Study Team (CCST) had a more focused agenda of preparing an Initial National Communication. Training modules on Vulnerability and Adaptation assessment became available from regional universities (Waikato University and the USP) which were attended by Kiribati nationals. A greenhouse gas inventory for 1994 was attempted and was included in Kiribati Initial National Communication.

After the completion of the PICCAP the Climate Change Study Team was temporarily inactive. However, the team was revived under the NAPA and KAP I projects. The NAPA and KAP I activities envisaged two committees for their management: the first is to provide policy direction for the projects, and the second to act as a technical committee. An Adaptation Steering Committee was formalized to give policy directions for the two projects, whilst the CCST deal with the technical works of the projects.

Due to a NAPA initiative, international advisors for the KAP were able to provide current climate tools for generating climate change scenarios. These scenarios were adopted in the Climate Change Adaptation Policy and Strategy that Cabinet approved. Prioritization criteria for NAPA proposed activities were also developed with the guidance of the advisors. In this way activities of the two projects were able to be harmonized.

Other capacity building initiatives have been undertaken over the years with support from a variety of development partners. The Climate Change Unit (CCU) of the ECD have benefited from regional trainings on various tools for assessing and planning for climate change impacts. In connection with the ADB consultancy on mainstreaming environmental concerns, a two day workshop was conducted for CCST members on climate change scenario generation based on past trends and incorporating global scenarios. Many members of the CCST and ECD staff attended a more recent training on the science of climate change and available tools and information on climate prediction and mainstreaming. Additionally, efforts have been made to strengthen the meteorological services. Through an Australian regional project, the Meteorological Division has been strengthened in its capacity to develop and issue climate predictions. More meteorological stations were upgraded through KAP II and these will be supplemented by KAP III.

Since the submission of the Initial National Communication in 1999, there had been observed growing interests by academic and international organisations on Kiribati future vulnerabilities to the adverse impacts of climate change. This was evidenced by the number of Vulnerability and risk assessment conducted on specific sectors in Kiribati. These studies form part of a critical body of information that inform not only the Government of Kiribati in terms of their adaptation approaches but also the regional and international communities.

The strengthening of regulatory measures for the management and conservation of the environment is recognized as a key form of adaptation. With this in mind, the Kiribati government has strengthened the Environment Act of 1999 in a superseding Act. In addition, there are a number of other pieces of legislation which have implications for environmental management. The KJIP has indicated that it will be necessary to have a more detailed review of these legislations with a view to harmonize their effects for more effective environmental management and to build climate resilience.

The NCSA report indicated that although broad-based stakeholder consultation has been undertaken under the various adaptation programs and initiatives, public awareness and some mechanisms to communicate on timely basis climate and climate change information to the general public is still required. Attempts have been made but not on a continual basis and without well designed approach and clarity on target audiences, and contents. The NCSA report indicates that the approach of the Government to addressing capacity caps is to address the root causes of those gaps. The Report identified the following gaps in capacity to manage risks from climate change:

This final report of the Kiribati National Capacity Self Assessment (NCSA) Project presents a concise summary of key capacity issues affecting national ability to adequately manage risks from climate change, including: inadequate information management, limited financial resources, limited capacity to communicate, educate and raise awareness on key issues and influence behavioral change, limited coordination and integration amongst agencies and stakeholders to address environmental and climate change issues, weak enforcement of environmental laws and regulations, limited capacity to access development opportunities, limited mainstreaming of environmental and climate change issues into national strategies, plans and programmes, limited use of traditional knowledge and practices in environmental management and limited capacity to cope with reporting requirements of the conventions. The report ends with a presentation of the main capacity development actions needed to address the cross-cutting environmental and capacity issues.

The Pacific Adaptation Strategies Assistance Programme – Kiribati National Stocktaking and Stakeholder Consultations Report (October 2011) indicates that although previous adaptation project undertaken in Kiribati have built some level of capacity to manage climate change and sea level rise issues, these efforts are often hampered by the following:

a) Lack of technical capacity and capabilities;

b) Lack of reliable data and information relevant for informing adaptation decision- making;

c) Lack of or low level of climate change and sea-level rise awareness at the community or village level;

d) Lack of leadership across the various sectors;

e) Lack of predictable resources to supplement the needs; compounded by,

f) Growing complexity of emerging political climate change issues.

The Kiribati Joint Implementation Plan on Climate Change and Disaster Risk Management

(KJIP) (2014) reports that the following capacity constraints are still to be addressed:

a) Only a few sectors have transferred strategic actions to address climate and disaster risks into their annual Sector Operational Plans and Ministerial Plans of Operations and budgeting.

b) Policies and strategies relating to human resource development, minerals and foreshore development, private sector development, investment, transport, communications, tourism and minerals do not explicitly consider climate change and disaster risks.

c) Most laws need to be reviewed as, with the exception of the Disaster Management Act 1995, they do not regulate responses to climate change and disaster risks and impacts.

MEANS OF IMPLEMENTATION

The effective implementation of the mitigation and adaptation measures will depend on timely accessibility, availability and provision of financial resources, technology and capacity building support. The provision of resources would build on, and where necessary, implement the various mitigation actions including grid-connected photovoltaic system under Japan PEC fund, the World Bank and UAE funds and continue with the implementation of the strategies and actions

espoused in the Kiribati Joint Implementation Plan for Climate Change and Disaster Risk Management (KJIP).

The Government of Kiribati intends to explore options for innovative and coordinated financing to implement the KJIP and community-based adaptation plans from varied sources such as multilateral and bilateral donors and regional and national funding mechanisms. Innovative financing approaches and operations will be explored, including options such as microfinance, carbon levies, subsidies, soft loans, emergency funds, sovereign insurance, contingent credit, catastrophe bonds, and intergovernmental risk insurance. Based on lessons learned and best practices from other SIDS such as Palau and the British Virgin Islands, the Government will investigate the viability of, amongst other measures: (i) setting aside the valued added tax (VAT) charged for fuel; (ii) charging carbon levies to offset greenhouse gas emissions for international air transport to the country; and (iii) charging fees for climate change research undertaken in the country. Such fees and charges will be used to establish and finance a climate change trust fund for priority climate change measures.

Additionally, the Government of Kiribati intends to build national capacity to facilitate direct access to international climate change financing including the Green Climate Fund so as to ensure that financing for climate resilience is country-owned and directed towards priority national needs and community-based adaptation plans. Based upon lessons learned from other SIDS, Kiribati will seek assistance under the “Readiness” program operated by the Green Climate Fund to establish the necessary legal, institutional and fiduciary management framework and accredit the National Implementing Entity (NIE) needed to facilitate direct access, thereby reducing dependence upon intermediary agencies for the design and implementation of priority adaptation interventions.

Indicative Costs and time line for provision of adaptation support

The KiribatiJointImplementationPlanon Climate Change and Disaster Risk Management (KJIP) (2014) reports that the overall gross indicative resource costs to implement the KJIP over the period 2013–2023 are estimated to be AUD 103,107,161 (approximately US$75 million). Of this total, it is estimated that financial cost constitutes 96% of overall costs while the in-kind contributions constitute 4%. The costs by strategy are summarised in the table below. These costs are to implement the next phase in a constantly evolving adaptation program being implemented by Kiribati.

The implementation of the KJIP is to be financed through already existing strategies ranging from national budgets and other internal sources to overseas development assistance, additional climate change funding and humanitarian aid. It is expected that a considerable portion of the necessary financing will be provided in the forms of grants from the Green Climate Funds, Global Environment Facility (GEF), Adaptation Fund, and from various bi-lateral climate change programs.

Addressing gaps in national, sector and community-level adaptation and climate resilience programs

Most national policies and strategies such as NAPA, KJIP, and others emphasise the importance of engaging the widest possible circle of stakeholders (including NGOs, CSOs and the private sector) in order to achieve their environmental objectives. Kiribati Government is supporting NGOs and CBOs in the elaboration of national strategies and plans. However, with a focus on top-down adaptation mainstreaming, the current national implementation mechanism has not ensured the greater synergy in the implementation, of community-based adaptation and climate resilience programs in alignment with national strategies and planning frameworks, so to effectively leverage the potential CSO and village communities’ perspectives and engagement. It is the intention of the Government of Kiribati that a community-based vulnerability mapping, adaptation planning and management approach (tied to improved access to financing for community-based resilience-building projects) be employed on a whole of island basis that will build capacity in vulnerable villages for small scale localised adaptation actions which represents a critical contribution to the implementation and achievement of these national Climate Change and Disaster Risk Management policies and strategies. The Government of Kiribati will establish the institutional structures and strengthen capacities at the community level in order to support the country-wide implementation of community-based vulnerability mapping and adaptation planning, and the community-based design and implementation of priority resilience measures through improved access to financing for such measures. By fostering broader community engagement and ownership in building climate resilience at the local level, it is anticipated that long-term support will be sustained for priority adaptation interventions that address the basis needs of vulnerable villages and segments of society.

The Government of Kiribati will also initiate measures to improve donor collaboration on climate change adaptation programming, and will establish the mechanisms for improved coordination amongst government agencies in the design and implementation of priority adaptation programs and projects as defined under the KJIP and community-based adaptation plans. A priority of the Government of Kiribati is to establish the Climate Change and Disaster Risk Management Unit in the Office of the President (working in collaboration with the Department of Environment) as the gatekeeper, coordinator and entry point for climate change programming engagement with all development partners to ensure that all projects funded by external sources support the implementation of the KJIP and community-based adaptation plans. In the exercise of this function and responsibility, the Office of the President and the Department of Environment shall ensure that international climate change programming supports the implementation of the KJIP and community-based adaptation plans.

Equity

The Republic of Kiribati is a smallest contributor to the greenhouse gas emissions by any measurable indicator and yet it is at the frontline of the wrath of climate change and sea level rise. Kiribati has a right to develop its economy and improve the well-being of its population. Thus Kiribati’s contribution towards limiting the global temperature to below 20C relative to pre- industrial levels provides a moral imperative as a global citizen. The government has embarked on a number of actions which will result in increasing the use of renewable energy technologies, improve energy security and reduction of GHG emissions. However, the main focus for long term sustainable development still remains adaptation to climate change by addressing the adverse impacts of climate change and its consequent sea-level rise.